This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Logging in with the fridge handle

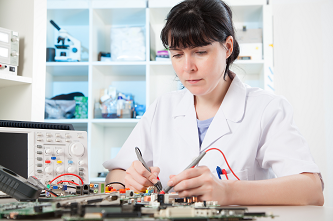

Researchers from ETH Zurich have investigated how everyday routines could be used for secure and user-friendly authentication – with no need for cumbersome passwords

A vision of the future: imagine you finish a long day of work and get back to your smart home, where you live with your family. In the hallway, you are automatically logged into the sound system based on the temperature of your feet and the place where you typically put your keys on the shelf. Your favourite music starts to play quietly in the background. In the kitchen, you go to get a cold drink from the fridge and the appliance recognises you from the way you squeeze the fridge handle, allowing you to open it without impediment. For your four-year-old child, on the other hand, the fridge would have remained closed.

Smart homes use information that they obtain via sensors, for example, to offer maximum convenience, efficiency and assistance to their inhabitants. Homes such as these are already a widespread phenomenon, though they are not yet as common in German-speaking countries. “At present, authentication is an additional hurdle and challenge for smart home users to overcome,” says Verena Zimmermann, psychologist and Professor for Security, Privacy and Society at ETH Zurich.

Logging into smart devices often requires users to enter a long password via a remote control or a small display, e.g. on a smartphone. This frequently leads to typos and is not user-friendly. “In particular, it can be difficult for older people, children and people with physical disabilities.” Together with researchers from Germany, Zimmermann looks at how the authentication of users in smart homes could be reimagined.

In a recently published external page study, the researchers describe how they worked with various groups of users to investigate how everyday and existing objects in the home could be used for logging in. To this end, they set up two “living labs” – a smart kitchen and a smart living room – and then asked the study participants to think about how they would interact with the objects in order to log in.

“One approach centred around the fridge handle,” says Zimmermann. “Ideas included squeezing the handle in a certain way, measuring the thumb temperature, moving the handle in a specific way, or pressing a specific sequence of buttons like on a piano. The participants had free rein.”